Why climate justice matters to India

For India, climate justice is not a slogan. It is a practical framework for balancing three imperatives at once: lifting millions into a dignified life, keeping energy reliable and affordable, and cutting emissions fast enough to help avoid dangerous warming. International law already recognizes the idea that responsibilities differ by history and capacity. The UN climate convention’s equity principle, known as “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” (CBDR-RC), says countries must act on climate “on the basis of equity.” India has consistently anchored its diplomacy in this clause, which is the first principle in Article 3 of the UNFCCC. Wikipedia

India’s emissions profile in context

India is the world’s third-largest emitter in absolute terms, but the fair-share debate hinges on per capita and historical emissions. India’s per-person CO₂ emissions are roughly a third to two-fifths of the global average depending on the dataset and year, and far below those of high-income economies. Public datasets from Our World in Data and the IEA show that global emissions hover just under 5 tons per person, while India’s per-capita energy-related CO₂ is around the 2-ton mark. Cumulative historical emissions are also dominated by developed regions. These facts shape India’s claim that development space and poverty eradication must be protected as mitigation accelerates. Our World in DataIEAIPCC

What India has pledged and delivered

At COP26 in Glasgow, India announced a net-zero target for 2070 and a package of 2030 pledges that included cutting the emissions intensity of GDP by 45% from 2005 levels and getting 50% of installed electricity capacity from non-fossil sources. The government later formalized these in its updated NDC and long-term strategy. Climate Action Tracker

Delivery has moved quickly in power capacity. In July 2025, the government said India had reached 50% installed non-fossil capacity five years ahead of schedule. That progress does not end the coal debate, but it shows the direction of travel in the power mix. Mongabay-India

Meanwhile, India has launched sectoral bets that align development and decarbonization. The National Green Hydrogen Mission targets at least 5 million metric tonnes of green hydrogen production annually by 2030, supported by large-scale renewable build-out and industrial pilots in steel, transport, and shipping. The Cabinet approved the mission in January 2023, with a multi-billion-dollar package to cut costs and crowd in private investment. Press Information BureauIndia Government

India also promotes demand-side change through Mission LiFE, a national and international push for “mindful and deliberate” consumption. It positions lifestyle choices and efficiency as complements to heavy industry decarbonization. NITI Aayog

Shaping coalitions, not just targets

India’s climate diplomacy has focused on building practical coalitions that solve problems for the Global South. Two examples stand out.

The International Solar Alliance (ISA). Launched with France in 2015, ISA is a treaty-based body headquartered in India that coordinates demand, finance, and standards to scale solar in “sunshine countries.” It formalizes South-South cooperation on technology, risk pooling, and procurement. International Solar AllianceUnited Nations Documentation

The Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI). Announced at the UN Climate Action Summit in 2019 and based in New Delhi, CDRI helps countries design, finance, and manage infrastructure that can withstand climate and disaster risks. This responds to a core adaptation gap in developing economies where physical assets are rapidly expanding. Sustainable Development Goalscdri.world

Together, ISA and CDRI speak to India’s preferred role: a bridge between advanced economies and developing countries, translating high-level pledges into pipelines of bankable projects and resilient systems.

Finance is the make-or-break

No matter how credible national plans are, climate justice will fail without capital at scale and on fair terms. The $100 billion per year promise from developed countries was meant to build trust. It was reached only in 2022, two years late, according to the OECD. The delay and the heavy reliance on loans eroded confidence, and the need now runs into the trillions. With negotiations moving toward a new collective quantified goal for finance after 2025, India and other developing countries want a larger, more predictable flow with a higher share of grants for adaptation. OECDReutersFinancial Times

India’s position has been blunt: developed countries should mobilize $1 trillion quickly to catalyze the transition in the Global South, and finance delivery should be tracked as closely as mitigation. That line was set out clearly by the Prime Minister in Glasgow. MEA India

Loss and damage: from promise to operation

Equity is not only about mitigation and adaptation. Countries are already facing irreversible climate losses. After years of pushback, a dedicated Loss and Damage fund was agreed at COP27 and operationalized at COP28 with the World Bank as interim host. In 2024 the fund appointed its first executive director, moving a step closer to disbursements. For India and its partners, the test now is whether the fund can channel money quickly to climate-vulnerable communities without onerous conditions. blogs.law.columbia.eduWorld BankReuters

The balancing act at home

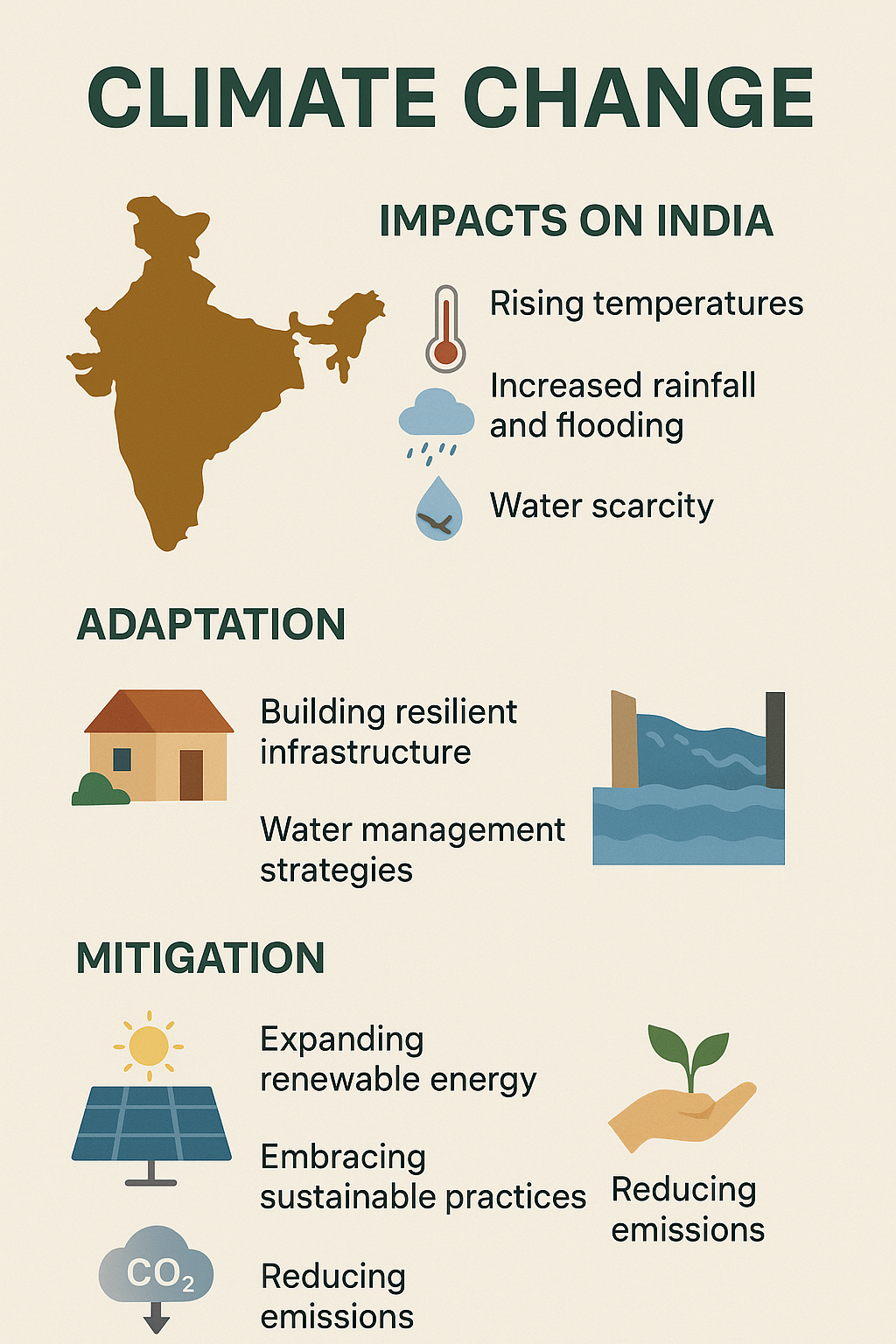

India’s development story is energy-intensive. Reliable power for industry, cooling for rising temperatures, steel for infrastructure, and jobs in manufacturing all require careful sequencing of the transition. That is why India frames coal not as a goal, but as a legacy challenge to be phased down in line with energy security and affordability, while ramping solar, wind, storage, and green hydrogen. Reaching 50% non-fossil capacity is a milestone, but the next test is integrating variable renewables, building grids and storage at speed, and cleaning up hard-to-abate sectors. Mongabay-IndiaIndia Government

What “justice” requires from the international system

If climate justice is to be more than rhetoric, three practical shifts must happen.

- Finance that fits risk. Concessional capital must flow where risk is highest and returns are public. That means larger multilateral balance sheets, guarantees that de-risk private projects, and rules that count grants fairly. The post-2025 goal should reflect actual needs, not what donors find convenient. India will continue to push for predictable, low-cost capital at scale. ReutersFinancial Times

- Technology that is affordable to deploy. ISA’s work on common standards and procurement, and mission-mode policies like green hydrogen, can cut costs through scale. But export controls, high licensing fees, and fragmented standards raise costs for developing countries. Coordinated efforts that treat clean tech as a global public good would accelerate diffusion. International Solar AlliancePress Information Bureau

- Resilience as core infrastructure policy. CDRI’s agenda should become default practice for new roads, ports, power lines, and hospitals in climate-exposed geographies. Every dollar spent on resilient design saves multiple dollars in disaster losses, but many countries still build to outdated standards. Embedding resilience in development finance can change that. Sustainable Development Goals

A fair pathway forward

India’s stance is straightforward. All countries must do more, but the pathway must be equitable. Developed economies need to cut faster and pay more. Emerging economies should bend their emissions trajectories through renewables, efficiency, and clean industry, backed by affordable finance and open technology. India will keep expanding coalitions like ISA and CDRI, scaling green hydrogen and renewables at home, and pressing for a finance deal that matches the size of the problem.

This is what leadership from the Global South looks like: action at home, coalitions that solve common problems, and a persistent insistence that justice is not an afterthought. It is the only way the world can hold the line on warming while development continues.