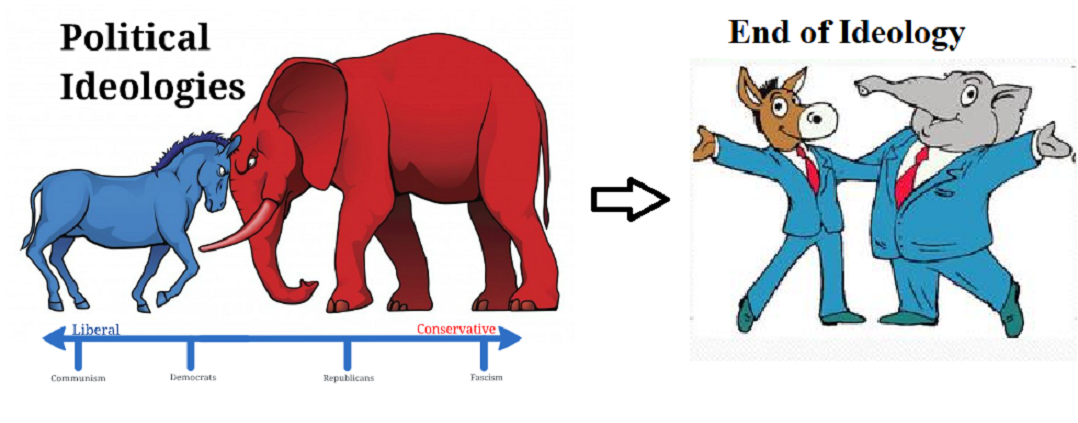

In the mid-1950s and 1960s, a significant discourse emerged regarding the status of ideology in the modern world. Intellectuals in Western liberal-democratic societies proclaimed that the age of ideology had ended, viewing it as a tool of totalitarian regimes rather than a feature of open societies. This notion posited that at an advanced stage of industrial development, a nation’s socio-economic structure was shaped more by technological progress than political ideology. Both capitalist and communist societies were expected to develop similar features regardless of ideological distinctions.

The Birth of the ‘End of Ideology’ Thesis

The concept gained traction after the 1955 Milan conference titled The Future of Freedom. Daniel Bell, a prominent figure in this debate, declared in his book The End of Ideology (1960) that a broad consensus had formed around the welfare state, decentralized power, a mixed economy, and political pluralism. Bell believed ideological frameworks had become irrelevant as societies evolved beyond them.

New Social Structures and Economic Development

Ralph Dahrendorf’s Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society (1957) expanded on this idea. He argued that Western societies had transitioned into “post-capitalist societies” where industrial and political conflicts no longer overlapped. In this new phase, industrial relations were institutionally isolated, diminishing Marxist theories’ relevance. Similarly, Bell observed that post-industrial societies experienced a growth in the service sector, a decline in industrial labor, and the rise of technical elites, independent of ideological leanings.

W.W. Rostow’s The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (1960) further supported this view. He proposed a universal model of economic development involving five stages, from traditional societies to high mass consumption, claiming that political ideology had minimal influence on a country’s developmental trajectory.

Technocracy and Bureaucracy in Advanced Economies

J.K. Galbraith’s The New Industrial State (1967) described common traits of advanced economies, including centralization, bureaucratization, and technocratization. He argued that in both capitalist and communist societies, power had shifted to a technocratic elite, reducing the influence of capitalists and workers alike.

The ‘End of History’ and Its Implications

With the fall of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 and the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History thesis gained prominence. He argued that liberal democracy had triumphed as the final form of human government, fulfilling humanity’s deepest aspirations. However, this view was critiqued for oversimplifying complex socio-political dynamics.

Criticism and Alternative Perspectives

Despite its wide acceptance, the end-of-ideology thesis faced strong criticism. Richard Titmuss pointed out the continued concentration of economic power, social inequality, and cultural deprivation under capitalism. C. Wright Mills denounced the thesis as a justification for the status quo and political complacency. He saw it as an ideological stance in itself, denying the relevance of transformative ideas. C.B. Macpherson criticized its failure to address equitable wealth distribution, while Alasdair MacIntyre argued in Against the Self-Images of the Age (1971) that the end-of-ideology narrative was a product of its own ideological context. Even, Fukuyama, in his latest book ‘Identity’, concedes that so-called ‘identity politics’ and the turn to global ‘tribalism’ now threatens to undermine his prophecy from 1989.

The ‘End of History’ Delayed: Yuval Harari

In addition to the aforementioned critiques of liberalism, the author highlights how the twin revolutions of biotechnology and information technology have put liberalism in a difficult position. The advent of artificial intelligence and the blockchain revolution may render humans increasingly irrelevant in the face of these transformative technologies. Competing governance models—such as China’s system, Russia’s oligarchic structure, or the rise of global Islam—might challenge the faltering liberal order. Alternatively, people may abandon the pursuit of a global narrative altogether, instead retreating into nationalist or religious ideologies. Examples include Trump’s “Make America Great Again” campaign or Islamist attempts to replicate the governance model of Prophet Muhammad. The pressing question is whether liberalism can once again adapt and evolve, as it has in the past, or if it is time to envision an entirely new guiding narrative for humanity.

Conclusion

The end-of-ideology thesis was instrumental in promoting the supremacy of liberal democracy during a time of ideological conflict. However, its claims require careful scrutiny. The collapse of socialism may reflect failures in its implementation rather than inherent flaws, and liberal democracies remain far from perfect models of justice. Human emancipation is multifaceted, requiring insights from diverse ideologies—liberalism, Marxism, socialism, feminism, and more. A balanced, critical approach to these ideas is essential for addressing modern societal challenges.